What is peptic ulcer?

- Ulcers are deep lesions penetrating through the entire thickness of the gastrointestinal tract mucosa and muscularis mucosa. Peptic ulcer is one of the common GI disorders. Some common types of peptic ulcer are duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer.

- The causes of peptic ulcer may be H. Pylori infection, increased gastric acid secretion, stress or NSAIDs.

What are proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and how they work?

- Proton pump inhibitors were clinically introduced in market more than 25 years ago and are still used as mainstay treatment for acid related disorders. They were first approved for use in 1989. Over the past several decades, PPIs have become one of the most commonly prescribed medications in the United states.

- When compared with earlier agents like systemic and non-systemic antacids, histamine receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and anticholinergics used in management of peptic ulcer, PPIs are quite beneficial as they possess superior acid suppressing capability, consistent patient tolerance and excellent safety.

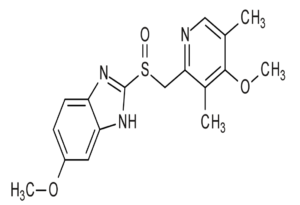

- All currently approved PPIs are benzimidazole derivatives, heterocyclic organic compound that include both a pyridine and benzimidazole moiety linked by a methylsulfinyl group. Omeprazole was the first clinically used PPI. Lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and the stereo-isomeric compounds esomeprazole and dexlansoprazole were subsequently introduced.

Figure- Structure of omeprazole

- PPIs are weak bases and are prodrugs which require activation at acidic pH. To prevent premature activation and degradation in luminal gastric acid, they are available in form of enteric coated tablets, gelatin capsules, coated granules as a powder for suspension or in combination with bicarbonates to temporarily neutralize luminal pH.

- They are absorbed in proximal small intestine, diffuse from blood into the parietal cells and accumulates in the acidic secretory canaliculi. The parietal cell possesses specific hydrogen-potassium-ATPase enzyme (proton pump) which is common final pathway for gastric acid secretion. They bind covalently to cysteine residues of the H+-K+-ATPase and inactivate it irreversibly leading to inhibition of gastric acid secretion. The effect last till enzyme is regenerated following stoppage of the drug.

Figure- Mechanism of action of PPI (Source- stewards.com)

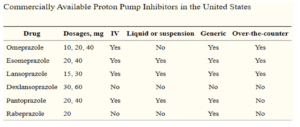

Figure- Commercially available PPIs in United States

Pharmacokinetics of Proton Pump Inhibitor

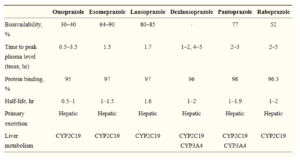

- In small bowel, PPIs are rapidly absorbed, highly protein bound. It is metabolized in liver by hepatic CYPs particularly CYP2C1 and CYP3A4.

- Currently available benzimidazole‐based PPIs have similar half‐lives of 1–2 hours. However, their duration of effect is longer than would be expected simply on the basis of plasma half‐life. Proton pump inhibitors are slow to achieve steady‐state inhibition of gastric acid secretion. With once daily dosing, it may take 2-5 days of therapy to achieve 70% inhibition of proton pump at steady state. Acid secretion is suppressed for 24 hours or more until new proton pumps are synthesized and incorporated in parietal cells.

- PPI require active expression of H+-K+-ATPases for binding which occurs in response to a meal. During a single meal, neither all parietal cells nor all their proton pumps are expressed. A single dose of PPI inhibits only about two-third of proton pumps so one-third of pumps remain uninhibited. With future meals, proton exchange will again increase. This physiology is the rationale both for pre-prandial dosing (important due to short serum half-life) and the observation of escalating pharmacologic efficacy of PPIs after multiday treatment.

- In case of hepatic diseases, clearance of PPIs may be reduced so their dose should be adjusted. In case of chronic renal failure, there is no accumulation of proton pump inhibitors with once a day dosing.

Figure- Pharmacokinetics of commercially available PPIs

FDA- approved uses of Proton Pump Inhibitor

- Treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcer.

- Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

- Used for treatment and prophylaxis for NSAIDs induced ulcer.

- Treatment of H. Pylori infection in combination with antibiotics.

- Management of pathologic hypersecretory condition (including Zollinger- Ellison syndrome).

Adverse effects of PPI

- Generally, it is well tolerated. GI disturbance, dizziness and drowsiness may occur.

- It inhibits the hepatic microsomal enzyme and prolongs the half life of drugs like diazepam, phenytoin, warfarin, carbamazepine etc.

- Prolonged use may increase incidence of osteoporosis. Chronic use of high dose PPI may affect absorption of calcium, magnesium and vitamin B -12. There is evidence that long term use of PPI increases patient’s susceptibility to enteric infections like small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, and Clostridium difficile infection.

- In 2011 the FDA issued a class warning based on 61 individual case reports indicating that prolonged PPI use could result in low magnesium levels. Although the exact mechanism responsible for associated hypomagnesemia are unknown, FDA recommends checking magnesium levels periodically in patients who are on prolonged PPI treatment or who take PPIs with medications such as digoxin or drugs that may cause hypomagnesemia (e.g., diuretics).

- Other recent FDA mandated PPI class warnings include PPI associated acute interstitial nephritis and the possibility of vitamin B12 deficiency with chronic (more than 3 years) daily PPI use.

Advances in PPI technology

- Currently available PPIs have two main pharmacological limitations; short plasma half-life leading to short duration of effect and the need for pre-prandial dosing.

- Numerous efforts have been made to improve these limitations. Tenatoprazole, the first imidazopyridine PPI, possess superior inhibitory activity on H+/K+ ATPase and a substantially longer half-life than currently available PPIs. While definitive trials of clinical efficacy are still unavailable, this revision to the structure of PPIs has intriguing future potential. Formulation of available PPI can be altered to overcome challenges posed by short serum half-life.

- Dual release dexlansoprazole is formulated to release drug in two separate pH-controlled phases. 25 % of the drug dose is liberated in the proximal small intestine at a pH of 5.5, with pharmacokinetics (peak plasma concentration of 1 to 2 hours) like traditional enteric coated PPIs. This is followed by a second release of remaining 75% of the drug dose in the more distal small intestine at a pH of 6.75 which provides a second serum peak at 5 to 6 hours after administration.

- To avoid the need for premeal dosing, stimulator of gastric acid secretor can be added along with PPIs. Succinic acid exhibits Penta gastrin like activity and has been FDA approved as a pharmaceutical excipient. In a preclinical trial of 36 healthy subjects, succinic acid combined with omeprazole (Vecam®) demonstrated significantly better nocturnal intragastric pH control than omeprazole alone. A Phase IIb clinical trial (NCT01059383) evaluating patients with heartburn is currently going on.

References

- Forgacs, I. and Loganayagam, A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008; 336: 2–3.

- Farley A, Wruble LD, Humphries TJ. Rabeprazole versus ranitidine for the treatment of erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial: Raberprazole Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000; 95: 1894–1899.

- Huang JQ, Hunt RH. pH, healing rate and symptom relief in acid-related diseases. Yale J Biol Med. 1996 ;69: 159–174.

- Sachs G, Shin JM, Howden CW. Review article: the clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(Suppl 2):2–8.

- Furuta T, Ohashi K, Kamata T, et al. Effect of genetic differences in omeprazole metabolism on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 129: 1027–1030.

- Ito T, Jensen RT. Association of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy with bone fractures and effects on absorption of calcium, vitamin B12, iron, and magnesium. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010; 12: 448–457.

- Lo WK, Chan WW. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 11: 483–490.

- Galmiche JP, Sacher-Huvelin S, Bruley des Varannes S, et al. A comparative study of the early effects of tenatoprazole 40 mg and esomeprazole 40 mg on intragastric pH in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005; 21: 575–582.

- Daniel S. Strand, Daejin Kim, and David A. Peura. 25 Years of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review. Gut Liver. 2017 Jan; 11(1): 27–37.

- Avinash K. Nehra, Jeffrey A. Alexander, Conor G. Loftus, Vandana Nehra. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Review of Emerging Concerns. Mayo Clinic proceedings. February 2018: 93(2): 240–246.

- Pharmacology and pharmacotherapeutics. Page no- 633-643.

- Goodman and Gillman Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Page no- 621-632.

- A textbook of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. Page no- 247-250.