What is leprosy?

Leprosy or Hansen’s disease (HD) is chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium Leprae. Although it is curable, it continues to be a significant health problem in many parts of the world. There were 219,075 new cases of HD reported in 2011, underscoring the persistent transmission of the disease despite an overall decrease in its prevalence. The disease is common in South-East-Asia, Africa and other tropical and sub-tropical countries. It mainly affects peripheral nerves and skin but can also affect eyes, mucous membrane, bones and testes. It is transmitted by prolonged and intimate contact with untreated, open lepromatous patients. Clinically, there are four main types of leprosy:

- Lepromatous (LL)

- Tuberculoid (TL)

- Indeterminate (IL)

- Dimorphic (borderline lepromatous leprosy-BL and borderline tuberculoid leprosy- BT)

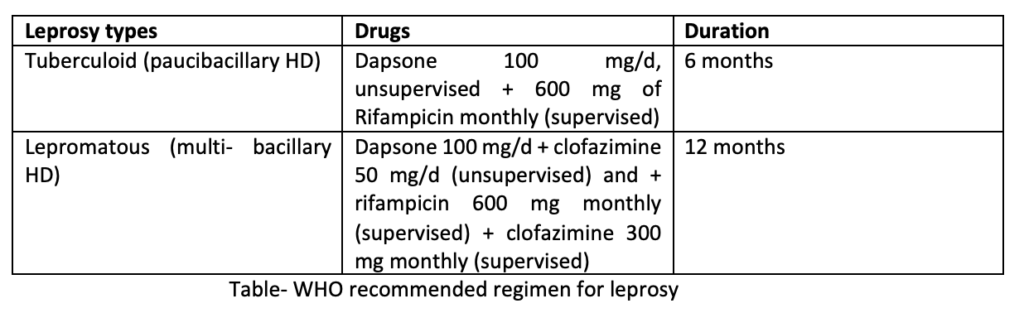

For therapeutic purpose, WHO classification of leprosy is;

- Paucibacillary leprosy(non-infectious)– TL and BT with 2-5 skin lesions.

- Multibacillary leprosy (infectious)– LL, BL with more than 6 lesions.

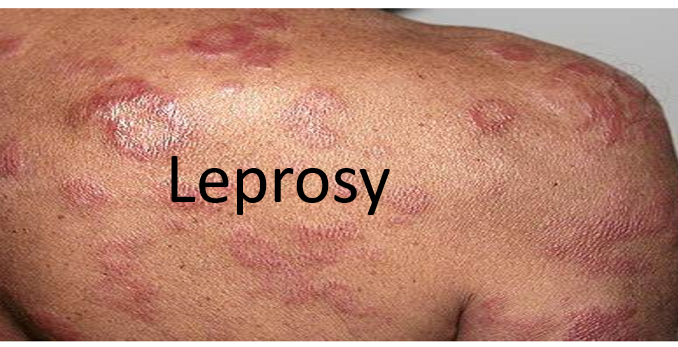

The common symptoms of leprosy are:

- Light colored or red skin patches

- Numbness and reduced sensation of touch

- Joint pain

- Weakness in the hands and feet

- Eye damage, reduced blinking

- Weight loss

- Hair loss

Management of leprosy

Most of the patients can be treated as outdoor patients, in mobile clinics or in primary health center. Only few patients need hospitalization. Patients with LL who are untreated or whom treatment has lapsed, should be isolated. Multi drug Therapy was introduced by WHO in 1981.

Combination of drugs is recommended to:

- Prevent drug resistance to monotherapy.

- Eliminate persisting organisms.

- Reduce the required duration of effective therapy.

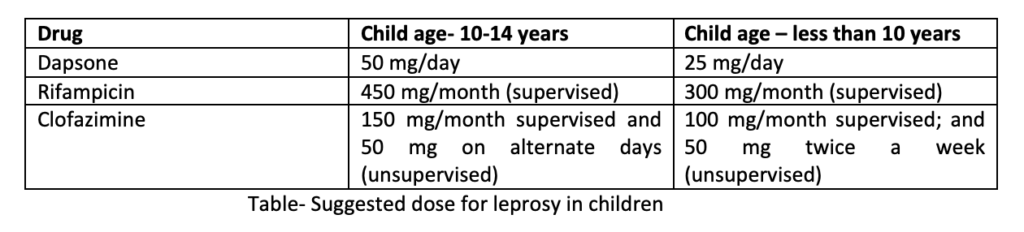

Drugs which can be used for treating leprosy are sulfones: dapsone, rifampicin, clofazimine, ethionamide/proethionamide, fluoroquinolones like ofloxacin, perfloxacin and other antibiotics like clarithromycin, minocycline. Rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine are the first line drugs in leprosy. All patients should receive a multidrug therapy as recommended by WHO.

For patients with paucibacillary HD having only one skin patch, single dose ROM treatment which includes rifampicin 600 mg+ ofloxacin 400 mg+ minocycline 100 mg is recommended. In children with similar condition, small dose is used. Such single dosage regimen is not recommended by other experts.

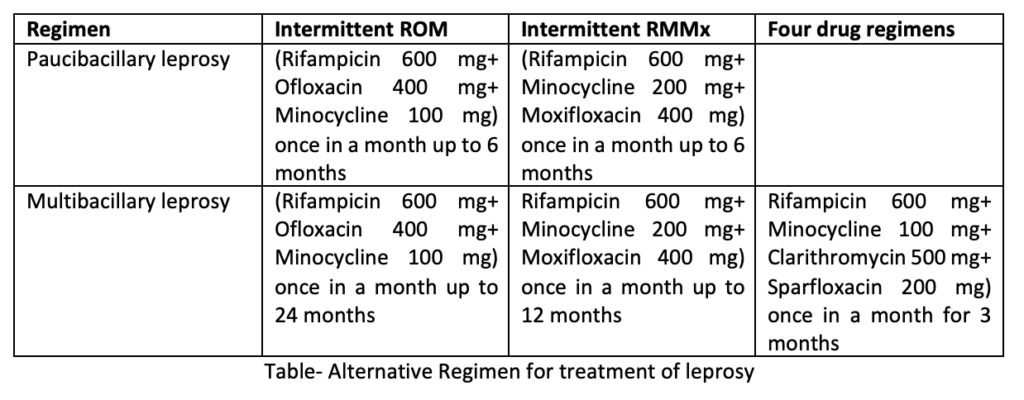

Alternative Regimens for treatment of leprosy are indicated in two cases;

- In dapsone resistance

- If MDT regimen is not advisable

The disease is considered inactive if for 12 months periods if:

- The disease is clinically inactive.

- Skin biopsies are negative for acid fast bacilli.

- No acid-fast bacilli are demonstrated by the slit-and-scrape samplings from the skin sites.

After MDT, the tuberculoid or indeterminant leprosy rarely recurs and usually no additional treatment is required after the clinical cure. Whereas in lepromatous leprosy, there is chance of recurrence so patient should be followed up at regular interval. The current challenge in leprosy therapy are poor compliance and rifampicin resistant strains.

Management of Lepra reactions

Lepra reactions results from changes in the immune balance between host and M. leprae. Such reactions are acute episodes which mainly affect skin and nerve and can cause death and nerve damage. They can occur during the natural course of disease, throughout treatment or after treatment. Lepra reactions are of two types;

1. Type I reaction (Reversal reaction)

It occurs due to delayed hypersensitivity and are related to cellular immune response against mycobacterial antigens. It can cause improvement or worsening of the disease. Existing lesions show increased erythema, swelling and tender peripheral nerves. Loss of nerve function may occur.

2. Type 2 reaction or ENL (Erythema Nodosum Leprosum)-

It is related to humoral immunity and is more severe than type I. Suddenly, many crops of bright erythematous nodules and raised patches appear and the existing lesions become worse. It may be associated with fever, iritis, neuritis, arthritis orchitis and lymphadenitis. It is difficult to treat, and lesions may spread.

While treating patients with lepra reactions, focus of treatment should be on controlling pain and inflammation and reversing nerve damage. Corticosteroids (prednisolone) are generally recommended. MDT can be continued with ant reaction drugs for both type of reactions. The earlier the corticosteroid therapy is started, the less will be the chances of permanent nerve damage. WHO suggests tapered dose of corticosteroids for over 12 weeks. Sometimes corticosteroids are used with high dose of clofazimine to control ENL. In patients who are intolerant to steroids, other immune-suppressive drugs like cyclosporine or methotrexate can be used.

Thalidomide possess important anti-inflammatory effect in type II reactions, but it is completely contraindicated in pregnancy and prescribed with caution in women of pregnant age due to its teratogenic effects. The loss of peripheral nerve function for 6 months or longer is classified as permanent nerve damage, and its management focuses on patient counseling and harm reduction. Clofazimine is given in the dose of 100 mg tid (3 times per day) for several days; and prednisolone in the dose of 40 mg/day x 2 weeks, 30mg/day x 2 weeks, 20 mg/day x 2 weeks, 10 mg/day x 2 weeks and then 5 mg/day. The treatment is continued for 3-12 months, depending on the severity of the reaction.

Antimicrobial drug-resistant M. leprae has been documented mostly with the use of dapsone in some areas of endemicity where dapsone has been used as monotherapy. Fortunately, there have been only a limited number of multidrug-resistant cases identified through representative mutations in more than two genes. Therefore, in comparison to the increasing concern of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MDT in patients with M. leprae infection continues to preserve its overall efficacy.

Prophylaxis for leprosis

One should avoid skin to skin contact with patients with LL having open lesions. Pus from ulcers is highly infectious. Airborne droplet infection is a distinct possibility. Antitubercular BCG vaccine has been shown to endow some protection against leprosy. In children with leprotic mothers, prophylactic dapsone at half the therapeutic dose is sometimes recommended.

References

- Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ. 2007. Leprosy. Clin Dermatol 25: 165–172.

- Graham A, Furlong S, Margoles LM, Owusu K, Franco-Paredes C. 2010. Clinical management of leprosy reactions. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 18:235–238.

- Polycarpou A, Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ. 2013. New findings in the pathogenesis of leprosy and implications for the management of leprosy. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 26: 413–419.

- 4. Cogen AL, Walker SL, Roberts CH, Hagge DA, Neupane KD, Khadge S, Lockwood DN. 2012. Human beta-defensin 3 is up-regulated in cutaneous leprosy type 1 reactions. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1869.

- Joel Carlos Lastória, and Marilda Aparecida Milanez Morgado de Abreu. Leprosy: review of the epidemiological, clinical, and etiopathogenic aspects – Part 1. An Bras Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr; 89(2): 205–218.

- An Brakel WH, Nicholls PG, Das L, Barkataki P, Suneetha SK, Jadhav RS, Madali P, Lockwood DN, Wilder-Smith E, Desikan KV. 2005. The INFIR cohort study: investigating prediction, detection, and pathogenesis of neuropathy and reactions in leprosy. Methods and baseline results of a cohort of multibacillary leprosy patients in North India. Lepr Rev. 76:14–34.

- Williams DL, Gillis TP. 2004. Molecular detection of drug resistance in Mycobacterium leprae. Lepr Rev. 75:118–130.

- Cassandra Whitea, Carlos Franco-Paredes. Leprosy in the 21st Century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015 Jan; 28(1): 80–94.

- Pharmacology and pharmacotherapeutics. Page no- 782-785.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559307/