Insomnia

- Physiologically sleep is regarded as absence of wakefulness, where responses to the environmental stimuli are greatly reduced. However, in fact, it is an active state related to definite anatomic structures, several neurotransmitters and biogenic amines.

- Insomnia is lack of sleep which may be due to different reasons. According to American Sleep- Disorders Association, insomnia is defined as “a repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation or quality that occurs despite adequate time and opportunity for sleep and results in some form of daytime impairment and lasting for at least one month”. A person with insomnia complains of inability to fall or stay sleep, decreased total sleep duration, sleep disturbed by nightmares. There are various deleterious effects of insomnia like decrease in quality of life and predisposition to several psychiatric disorders. Insomnia is more common in women than in men. Its prevalence increases with age affecting approximately 50 % of the elderly population.

- Insomnia can be classified into 3 different types;

-

- Transient insomnia: It lasts less than 3 days and is caused by environmental or situational stress.

- Short-term insomnia: It lasts from 3 days to 3 weeks and is caused by personal stress such as job problems, grief etc.

- Long-term insomnia: It lasts for more than 3 weeks with no specific stress.

General principles of management of insomnia

It is very important to exclude causes of insomnia that require treatment in their own right. These causes include:

- pain (e.g. due to arthritis or dyspepsia)

- frequency of micturition

- full bladder or loaded colon in the elder person

- dyspnoea (as a result of cough, bronchospasm or left ventricular failure)

- drugs like caffeine, nicotine, amphetamines

- alcohol withdrawal and benzodiazepine withdrawal

- depression

- anxiety

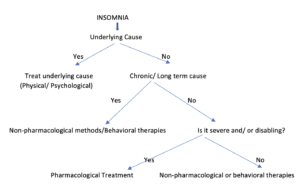

Figure- Decision tree/ Flow chart for the management of insomnia

Non-pharmacological therapy for treating insomnia

- In almost 30 % of cases, simple, non-pharmacological measures may help patients to establish good sleep habits. Non-pharmacological measures include behavioral therapies, CBT-I treatment and educating patients.

- Behavioral therapies include bedtime restrictions, stimulus control therapy and relaxation and education about sleep hygiene. Bedtime restrictions involve reduction in time spent in bed. Stimulus control focuses on having patients go to bed only when sleepy and avoid staying awake in bed for prolonged periods of time. Patients are instructed to leave bed if they are not asleep within 20 minutes and to engage in relaxing activity until they feel sleepy again.

- Relaxation training includes trainings like progressive muscle relaxation, abdominal breathing. CBT-I treatment combines cognitive therapy with behavioral interventions such as stimulus control or sleep restriction. Cognitive therapy helps patients to change their beliefs and unrealistic expectations about sleep. Specifically, for patients with chronic pain who are experiencing insomnia, a hybrid approach involving CBT-I combined with pain management programs has been suggested.

- Educating patients with insomnia about good sleep hygiene is common non-pharmacological intervention. The good sleep hygiene education should be performed in conjunction with stimulus control, relaxation training, sleep restriction, or cognitive therapy. The elements of good sleep hygiene are:

Do’s

- Establish a regular bedtime hour.

- Do moderate exercise in the morning or afternoon.

- Having some drinks like a glass of warm milk may help in reducing the time to onset of sleep.

- Establish good sleep environment such as quiet, cool and dark room.

- Develop relaxing habits like taking hot water bath before going to bed.

- Go to bed only for sleeping and when feels sleepy, one shouldn’t remain in bed if not sleepy.

- Keep the clock out of sight to avoid frustration at night when you look at it.

Don’ts

- Avoid daytime nap.

- Avoid consumption of alcohol, tobacco and caffeine near bedtime.

- Should avoid complex mental activity before bedtime.

- Avoid heavy meals and drinks 2-3 hours before bedtime.

- Avoid medicines that may disrupt sleep like diuretics.

- Also avoid lying in bed awake.

- Avoid going to bed hungry and avoid having oily, greasy food before bedtime.

Pharmacological Therapy for Insomnia

Choice of drug therapy depend on different factors like sleep patterns, specific symptoms, previous response to treatment, comorbid conditions, cost, treatment goals, potential adverse effects and drug-drug interactions. FDA approved prescription medicines for insomnia are:

- Benzodiazepine receptor agonists: Currently 5 benzodiazepine (BZD) agents are approved by FDA which are triazolam, estazolam, temazepam, quazepam and flurazepam. Non-benzodiazepines (non-BZD) agents also known as Z drugs like zolpidem, eszopiclone and zaleplone were developed to minimize adverse effects and abuse potential of BZDs.

- Melatonin agonist: Ramelteon which act on MT1 and MT2 It don’t act on GABA receptors so don’t have potential for abuse.

- Tricyclic antidepressant: Doxepin which have high affinity for histamine (H1) receptors.

- Barbiturates: like phenobarbitone, pentobarbitone are FDA approved but not recommended because of their significant adverse effects.

- Orexin receptor antagonist: Suvorexant was approved in August 2014 by FDA for treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep onset or sleep maintenance.

Off-label treatment of insomnia:

- Antidepressants like trazodone, mirtazapine which are approved for treatment of depression can be used off-label as a hypnotic at small doses. Atypical anti-psychotics like olanzapine, risperidone, although not recommended by FDA are commonly prescribed for sleep disorders.

Over-the counter medicines:

- 1st generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine, doxylamine are available over the counter as sleep aids due to their sedative properties. They are safe for treating mild insomnia, but evidence of efficacy is lacking. Melatonin is available over the counter primarily as nutritional supplement but also can be used to treat insomnia caused due to secondary causes like jetlag.

- BDZ receptor agonists are preferred more because of their efficacy, safety, tolerability and flexible pharmacokinetics. If a person is suffering from sleep onset insomnia short acting BDZ (due to their rapid effect) should be administered 20-30 minutes before the bedtime. For person with difficulty in maintenance of sleep longer acting drugs like lorazepam are preferred. Benzodiazepine with long half-life are preferred when daytime sedation is also required. BDZ can be substituted with antidepressants like doxepin which do not cause dependence and drug abuse. In elder persons, benzodiazepines should be used with caution because of increased risk of falls.

- Whichever hypnotic is used, its initial dose should be small and should be increased only if absolutely necessary. Once a good night’s sleep is obtained, attempts should be made to omit the drug for few nights. Patients should be warned about hangover which is a major drawback of hypnotics and about possible interaction of hypnotics with alcohol and other drugs. Patient receiving long term sedative-hypnotic should be followed and reevaluated every 6 months. If patients do not respond to initial therapy, another agent belonging to same class should be used after careful consideration.

- Insomnia caused by major psychiatric illness responds to specific pharmacological treatment for that illness. In insomnia caused due to depression, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can be used to produce improved sleep. If patients with chronic pain are suffering from insomnia, sedative antidepressants can be used as antidepressants have analgesic effects.

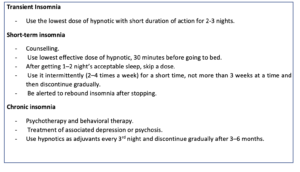

Transient Insomnia

- Use the lowest dose of hypnotic with short duration of action for 2-3 nights.

Short-term insomnia

- Use lowest effective dose of hypnotic, 30 minutes before going to bed.

- After getting 1–2 night’s acceptable sleep, skip a dose.

- Use it intermittently (2–4 times a week) for a short time, not more than 3 weeks at a time and then discontinue gradually.

- Be alerted to rebound insomnia after stopping.

Chronic insomnia

- Psychotherapy and behavioral therapy.

- Treatment of associated depression or psychosis.

- Use hypnotics as adjuvants every 3rd night and discontinue gradually after 3–6 months.

Table – Principles of drug therapy according to type of insomnia

References

- Reeve K, Bailes B. Insomnia in adults: etiology and management. J Nurse Pract. 2010; 6(1): 53-60.

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):487-504.

- Tang NK. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep abnormalities of chronic pain patients. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009; 11(6): 451-460

- National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. In Brief: Your Guide to Healthy Sleep. Accessed April 7, 2020.

- Dopp JM, Philips BG. Sleep disorders. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 8th ed.

- Vincent Mysliwiec, Jennifer L. Martin, Christi S. Ulmer, Susmita Chowdhuri,, Matthew S. Brock, Christopher Spevak, James Sall. The Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Synopsis of the 2019 U.S. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 172(5): 325-336.

- Hrayr Attarian, Margaret Kay-Stacey. Advances in the management of chronic insomnia. BMJ 2016; 354: i2123.

- Thomas Unbehaun, Kai Spiegelhalder, Verena Hirscher, and Dieter Riemann. Management of insomnia: update and new approaches. Nat Sci Sleep. 2010; 2: 127–138.

- Gregory M. Asnis, Manju Thomas,and Margaret A. Henderson. Pharmacotherapy Treatment Options for Insomnia: A Primer for Clinicians. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Jan; 17(1): 50.

- Janette D. Lie, Kristie N. Tu, Diana D. Shen, and Bonnie M. Wong. Pharmacological Treatment of Insomnia. P T. 2015 Nov; 40(11): 759-768, 771.

- David N Neubauer, Seithikurippu R Pandi-Perumal, David Warren Spence. Pharmacotherapy of Insomnia. Journal of Central Nervous System Disease Volume 10: 1–7.

- Pharmacology and pharmacotherapeutics. Page no- 123-140.

- Goodman and Gillman Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Page no- 262-277.

- A textbook of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. Page no- 104-107.